Escaping the cities of Tokyo and Kyoto, I take a train from Osaka to reach the Wakayama Prefecture, one of Japan’s larger districts, though with a smallish population of just a million. It’s effectively one huge dense forest of giant cedar trees that stumble all their way down to the Pacific Ocean. Tourism has now surpassed her timber industry and while it’s utterly in another world from, it’s highly accessible to, both Osaka and Kyoto.

I begin by getting a steep lift several thousand feet up to the citadel Koyasan, a centre to Shingon Buddhism, a primitive ancient sect that came straight from India, that is home to an active monastic centre with 117 temples, and a separate college for monks. Here, I stay at Hotel Souji-In, a ‘shukubo’ temple lodging originally for itinerant monks but now taking tourists, with delicious but simple traditional vegetarian food known as ‘shojinryori’ including sesame tofu, turnips, bean curd, pickled cabbage and grated ginger. Sitting cross-legged, I find my dining becomes an event in itself, a mindful experience that is more a ritual than simply an act.

It’s an enchanting lodging with its own tranquil stone-raked zen garden. My suite of rooms has ‘tatami’ mats and ‘fusuma’ sliding doors of wood and heavy paper. All very authentic and, along with the sublime food, I experience at first hand, the lifestyle of a Buddhist monk with an evening curfew imposed at 7.30pm, before the option of an early morning chant.

In Koyasan I visit the Danjo-Garan Sacred Temple Complex, an early 9th-century secluded sanctuary where monks trained. It’s a big vermillion temple with a steep staircase-cum-ladder and has gorgeous depictions on the pillars and in the corners; in the courtyard is an unusually white pagoda with an impressively huge bell. Within are screens of the four seasons symbolised by iris, maple, cherry and peony motifs along with those of cranes and turtles suggesting longevity. Outside is Japan’s biggest rock garden composed of two dragons entwining and embracing the home of the Emperor’s daughter, and where once the Dalai Lama was to stay. It stops me in my tracks and creates a moment of contemplation that has a pacifying effect upon me, as I observe it for longer than usual. Not a footprint in sight on this highly-groomed plot.

I take a mesmeric early evening stroll down Japan’s largest and two-kilometre-long Okuno-in cemetery. It’s lined with over 200,000 gravestones beneath towering cedar trees and ends with a mausoleum to Kobodaishi Gobyo who after 1,200 years, legend has it, is still thought to be meditating. The atmosphere is too historic to be spooky as the trees muffle the sound and shade the tombs to give it a peaceful, dreamy, film-like landscape.

The moss growing on the tombstones accentuates the cycle of life and I can only imagine the early morning mist and birdsong. Life and death in stark contrast.

It’s all a very sensual experience. The ancient tombstones are like chess pieces with their ‘gorin-to’ five-ringed towers representing, from the bottom up, earth, water, fire, wind and sky. There are lanterns for those recently departed and ‘Jizo’ offerings of statues with bibs to watch over children in their afterlife in similar fashion to Christians’ St. Christopher.

On I go the next morning to the Kumano region: home to three of Japan’s most sacred ‘grand’ shrines and linked by a network of five different ancient pilgrimage routes. The formalised ‘Mode’ Kumano pilgrimage is over 1,000 years old and where pilgrims visit in order to train their souls to reach paradise at these three ‘grand shrines’. There are walking itineraries that vary in length from several hours to several days. My shortened version is the last part of the most popular approach from Hosshinmon-oji to Kumano Hongu Taisha.

It is a stunning, long, mild and manageable descent on well-trodden paths beneath giant dense cedar trees with clearings through the forest offering a sunlit day in the most enchanting way. It is a divine walk amongst tea plantations and beside hamlets where now only the elderly work the land, past persimmon trees and yellow rice fields that resemble tatami mats in both their shape and colour.

I see black kites, egrets and herons but not the resident badgers, deer, boars or bears. I smell the sweet incense from the temples and heard the hourly chimes from the villages and the gongs of the nearby shrines. All very uplifting.

Deeply rooted in the Shinto religion is a sense of nature worship with trees, mountains, rocks and rivers considered ‘kami’ deities. Trees are deemed divine residences for Gods and are often seen with a ‘shimenawa’ rope to mark them as sacred. The ‘prefecture’ (district) of Wakayama abounds in nutmeg, elm, camphor, pine, cedar, cypress and bamboo: the last being, strictly speaking, a species of giant grass and not a tree.

I get a clear sense of ancient pilgrims from seeing modern day ones en route wearing their customary white clothes. I climb to sit on a hill to look down at the promised finish: the world’s largest ‘torii’, at 34 metres tall, called Otorii. Sometimes the simplest design is the most impactful. It’s a gateway arch that’s lit up for special festivals and isolates the shrine from the outside world. Torii were originally bird perches on which live cockerels were offered to the sun goddess.

Then I reach Kumano Hongu Taisha whose ‘grand shrine’ is the finish for all the pilgrimage routes. It’s ironic that Hongu means ‘authentic shrine’ as the pavilions have been rebuilt as a result of fires and floods. But it’s a great example of Japanese shrine architecture with the use of natural unfinished materials allowing it to blend effortlessly with the environment. Few nails are used as it relies solely on the intricacy of its joint work. There are the characteristic gabled roofs with decorated tile ends; bronze ornaments on the rooftops with ‘chigi’ X-shaped forked finials and ‘katsuogi’ log-like beams adding a dramatic highlight to the green malachite roofline while the orange vermillion shows its Chinese influence and, with its mercury, helps repel the insects.

Japan is rich in symbols and Yatagarasu, the sacred three-legged crow, appears in each of the three grand shrines: a trinity representing Hongu as the son and future, Nachi the mother and present, and Shingu the father and past.

From the monks’ cassocks of Koyasan to the guests’ green dressing gowns to the family friendly hotel called Kawayu Midoriya. It has a geological thermal marvel that attracts the indigenous visitors to its natural ‘onsen’ (the famous Japanese country inn) on the Oto river. The Japanese bathe together as one in the natural hot pools beneath the clear stars at night and the mist in the morning as the clouds lift like curtains rising. They are certainly in their element.

I come next to Kumano Hayatama Taisha and reached the Kamikura-Jinja Shrine by a steep ancient stone-paved staircase rising to quite a height. It’s a fun but challenging ascent with climbing sticks provided. I imagine the feet of pilgrims on this tricky stony paved climb. It’s famously the scene of the Oto Matsuri fire festival on February 6th, the New Year in the lunar calendar, when two hundred men in white clothes eat only rice, tofu and white fish to attain a spiritual cleansing.

And here’s the precarious Gotobiki-iwa rock against which pilgrims stretch out their hands to offer their blessings in the hope of preventing the fiasco of it toppling down. For this would both symbolise, as well as doubtless bring, death and destruction to the town of Shingu below. The scenery is dramatic and aethereal with teal-coloured water flowing and a mist descending on the deep, dark, dense forests.

I then reach the third of the ‘grand’ shrines, Kumano Nachi Taisha, a spiritual compound with Japan’s biggest gong. I loved the giant camphor tree ‘Nagi-no-Ki’ which is over a thousand years old, and hollow on the inside. I climb the Daimon-zaka slope, another pathway paved with layers of ancient stone, before getting to the top of the Seiganto-ji pagoda to get a wonderful view of Japan’s tallest waterfall Nachi-no-Otaki, a sacred cascade descending magnificently from the mountains as if connecting this world with the spiritual cosmos. Legend has it that the carp (koi) swim up to the top to change into a dragonfly as a symbol of promotion. I naturally drink eagerly from its water for the hope of longevity.

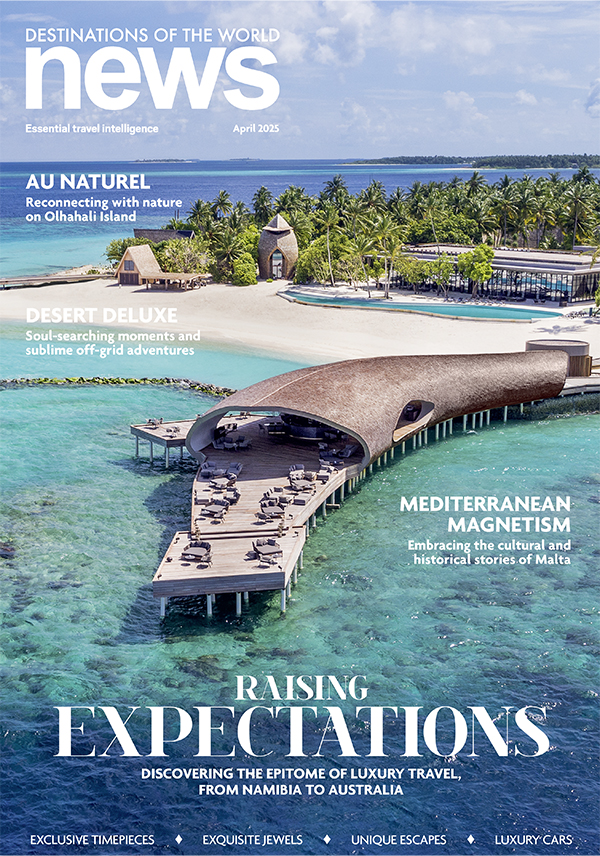

I stay last at the luxurious Infinito Hotel Nanki-Shirahama. It boasts both Japanese and Western-style suites and cuisine but its real claim to fame is the stunning panorama out over an ocean scattered with boats, rocks, inlets of fishing communities and white-sanded beaches: all of which attract the eager hordes of Japanese holidaymakers showing a respect for tradition and sacredness and a love of symbolism and collectivity. Japan in a nutshell.