“Can you hear it?” our guide Lucy whispers as we stand in the shadow of towering bamboo trees. It’s not some rare wild animal we’re tracking, rather the creaking sound made by this sustainable natural resource as it grows, especially after torrents of hot rain. The forest revitalised, this is also the ideal time to partake in a nature walk. I crane my neck to see a giant golden orb spider web glisten with rain droplets, strung between two soaring banyans that have been here since the time immemorial.

I’m on Nikoi – the private playground-turned-tropical island refuge of Australian expat Andrew Dixon and his American co-founder, Peter Timmer. Bordered by Singapore and Malaysia, barely one degree off the equator, it’s one of 1,800 islands cast like emeralds into the South China Sea in Western Indonesia’s unsullied Riau Archipelago. With its thriving equatorial nature, Nikoi feels light years away from the Lion City, despite only being two-hours from skyscraper to sand. It’s a realisation that Andrew and five friends came to in 2004 when they chanced upon the diminutive outcropping. What began as a time-share island for extended weekend city escapes has evolved into a fully-fledged island resort fifteen years later.

Just the antidote for the over-stimulated 21st-century traveller, its 20 duplex stilted villas epitomise Nikoi’s laissez-faire approach to barefooted lux. Its sand-in-the-toes bar and restaurant, tennis court, tented safari spa and accommodation cover just one third of the island. The remaining 10 hectares are a wildlife sanctuary where prehistoric-like Monitor Lizards lazily patrol its granite boulders, Great Mormon butterflies dance at dawn and 200kg green turtles find refuge on its beaches. Nikoi’s sustainably minded owners have introduced a raft of fauna and flora-friendly ‘non-disruptors’, from kerosene yellow lights to nurture its nocturnal crab population, to DIY mosquito traps, which negate the need to fog the island with polluting pesticides.

I discover the perfect bird watching hide is my thatch-canopied sala, nestled just a few barefooted steps from the beach, where collared kingfishers flit between native sea almond trees. I float between here and a swinging daybed in the sand-floored lounge of my two-storied villa - a treehouse for grown ups that does away with the formality of keys and channels a pared-down rustic island aesthetic. This extends upstairs, where tropical architecture capitalises on the island’s natural light and buffeting trade breezes, with an ocean-facing verandah and double-vaulted alang-alang roof. “These sustainable grasses last around six years before needing to be replaced, rather like England’s traditional straw thatching,” Lucy explains.

The archipelago’s original eco trailblazer holds up well against sustainable newcomers, utilising UV treated recycled water, solar-powered showers, food waste composting and reclaimed wood to build the resort from the sand up. The ultimate upcycling example has to be its beachside restaurant’s communal dining tables - hewn from a massive teak tree salvaged 100km out at sea.

I graze on an Indonesian platter of beef rending, prawn sambal and yellow rice as part of Nikoi’s locally sourced (and in some cases island-foraged) seasonal set menu. Up to 40 per cent of Nikoi’s cuisine is provisioned by their permaculture farm on the province’s island capital of Bintan – a former pirate hideout and centre of the crucial Indo-China trading route in the 16th century. Bebe: a frustrated urban gardener from Kuala Lumpur, cheerfully tours guests around his three-hectare plot on the island. We watch as iridescent dragonflies dance between trellised passion fruit vines and fruit laden orchards. “Dragonflies are a good barometer for water quality on the island,” Bebe explains. He and his team of five practice multiculture (versus monoculture) with crops like cashew nut, chillies, wing beans, papaya and passion fruit (which we’re encouraged to pluck straight from the vine). As well as tending to 700 free-range chickens, the maverick farmer is trialling cool weather crops like carrots, cacao and avocado that have never sprouted in Bintan’s unfertile rusty red laterite soils. Despite being banned in 2007 after 70 years of exportation, illicit mining of bauxite continues on the island.

On the western fringes of Bintan, the former quarry of Gurun Pasir Busung is now a surreal Saharan-like desert-scape of rolling sand dunes and aquamarine lagoons, that’s become an unlikely tourist attraction. The island’s abandoned red brick domed charcoal kilns, meanwhile, are an example of how conservation can triumph over commerce. Now an outlawed practice, these rumah arangs were used to burn mangrove wood into charcoals in the ’90s, before the environmental value of such coastal ecosystems was understood. Visitors can take a serene boat ride through protected mangrove forests along Bintan’s Sebung River. My own watery explorations involve a quick pompon (water taxi) to nearby Pulau Penyengat to marvel its grand palace ruins and royal mausoleums from the island’s sultanate era.

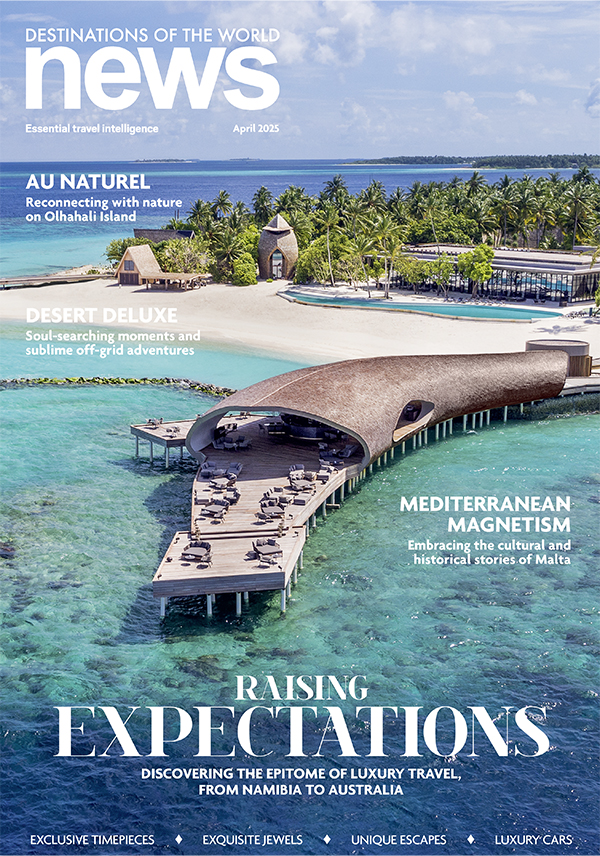

A half hour scenic speedboat ride from here is Cempedak (pronounced ‘Chempedak’) – Nikoi’s adults-only sister isle, where the tides of time and travel roll even more languidly. Silence is followed by a collective ‘ooh’ and ‘aah’ as the lush green isle emerges on the horizon, lapped by turquoise waters.

Tucked deftly between its thickets of jungle are 20 scallop-thatch roofed villas. No sooner have I shucked off my shoes and I’m padding around my very own duplex hilltop hideaway and relishing the simple pleasure of an outdoor shower.

The ‘pinch-me’ moment is standing on its balcony overlooking my private teardrop plunge pool, with swaying palms framing postcard views of the come hither sea.

An ode to bamboo, the villa’s other natural charms - copper, bronze and lava stone - are layered with reclaimed teak furnishings and luxuriant Pierre Frey fabrics.

Some 10 different bamboo species were used in the construction of the resort, from the restaurant’s snaking canopied walkway to the Dodo Bar’s bamboo straws, crafted by a family on nearby Bintan. These reusable straws are just one way both Nikoi and Cempedak are supporting local household cottage industries.

Raised deep in the Sulawesian jungle, my guide (an authority on all things bamboo!); Jaslan, is just the man to guide me through Cempedak’s very own wild interior. Our forest soundtrack this morning is a chorus of olive-winged bulbuls. “There are around 60 species of birds here,” Jaslan tells me. One is the territorial Stork-billed kingfisher, whose jealously guarding Cempedak’s tilapia fishpond. A flash of blue, green and copper plumage in nearby bushes reveals another… “That’ll be the closest living relative of the Dodo” Jaslan remarks matter-of-factly. We may not get to marvel the Nicobar pigeon in all its resplendent glory today, but I do catch a glimpse of the island’s indigenous Oriental Pied Hornbill from Mangrove Bay. This was a favourite lookout of Singaporean naturalist Subari Raj, whose driftwood memorial bench makes for a perfect pew to observe Cempedak’s family of frolicking ocean otters at sunset (rumoured to be island hopping at the moment!).

Nearby, a harmless, aerobatic Paradise tree snake has emptied the spa of its robed guests. It’s one of several rare critters that call Cempedak home, including the critically endangered pangolin (nicknamed ‘walking artichokes’) - famous for being the world’s most trafficked animal. “Fruit flies around the entrance signals there’s someone home!” Jaslan whispers as we crouch around a hole burrowed at the base of a granite boulder. These elusive nocturnal mammals are fans of Cempedak’s leaf-carpeted slopes, where they can hide or flee from prey by free-style rolling!

Also teeming with life are the island’s azure waters – a marine protected area, where Hawksbill and Green turtles visit between April and August and Indo-Pacific Humpback dolphins return after the monsoon rains. One of its more mysterious underwater creatures is the dugong – an endangered species of sea cow (more closely related to elephants than whales) that have been mercifully slayed for their tears and tusks.

One of the more offbeat tours that Cempedak curates enables guests to spend time with a fifth-generation reformed huntsman of these gentle giants on neighbouring Glubi Island. Semi-nomadic sea gypsies called Orang Laut (Malay for “sea people”) continue to practise age-old skills of catching fish and making boats and nets by hand. We sit cross-legged on the floor of Pak Munsa’s traditional stilted sea gypsy abode, where his 11 grandchildren excitably run around. Hands outstretched, the eldest shows me a slippery octopus – bait for fishing that supports the Munsa household these days. The seventy-something-year-old has the biceps of a body builder half his age I remark. “That’ll be years of spear throwing,” he explains. In his dugong hunting days, Munsa would hurl a spear 50 metres “like a javelin” from his canoe. The key to being a stealth hunter is having a good ear - a skill he began honing from the tender age of 14. The louder females are the most desirable catch, owing to their longer tusks, which command $1,300 a pair on the black market. Now an advocate for the conservation of these vulnerable marine mammals, Pak Munsa admits: “Just last week someone offered me dugong meat, but I refused.”

Back at the mosaic decking of Cempedak’s beautified boathouse pool sits the skull of a female dugong – a sobering reminder of the fragility of nature in even protected regions of the world. As I work up a sweat kayaking from here to Eagle Rock (named after the island’s three species), Jaslan makes the point that silver leaf monkeys can paddle all the way from neighbouring Poto Island to Cempedak’s shores! Driven out of Singapore’s forests decades ago, these arboreal residents have adapted well to island life.

The sundowner at shaggy roofed Dodo bar still feels well-deserved, as does the veritable three-course feast of calamari salad, pan fried slipper lobster with squid ink pasta and dragon curd meringue pie, devoured in the restaurant’s sea-sprayed dining pods.

My final morning is spent indulging in the very British pursuit of croquet with staff and guests on Cempedak’s immaculately manicured lawns. It doesn’t take long for two lumbering Monitor Lizards to hijack the court, forcing us to abandon play - a reminder that ultimately (and satisfyingly), nature has the final word here.