The golden era of travel in the 1950s put previously untouched places on the map for the first time. With the advent of the commercial plane — itself an extraordinarily glamorous experience, complete with cocktail lounges, gold-plated cutlery and passengers dressed up to the nines in impractical swathes of Dior’s New Look — the term ‘jet set’ was born.

From Bodrum and St Tropez to Cannes and Capri, film stars, musicians, artists and models dispersed to warmer shores all over the world, turning sleepy fishing villages into havens of glitz and glamour. Today many of these formerly unknown paradises have evolved into exclusive playgrounds for the elite, complete with mega yacht marinas, designer shopping outlets and Michelin star fine dining.

The small Greek island of Hydra was another destination favoured by the glitterati of the early 20th century and has long been regarded as the old-money Mykonos, its more flash, garish counterpart. Just two hours’ boat ride from the port of Piraeus in Athens and with a population of roughly 2,000, Hydra has remained refreshingly unchanged over the decades since its international discovery. With cars prohibited on the island, donkeys are still loaded up with supplies at the bustling port at dawn as they have been for centuries. In winter, next to the waterside festive displays, the whole scene resembles a bizarre nautical nativity scene. Behind the harbour is a rising amphitheatre of yellow mansions with red-tiled roofs set into the hills, bougainvillea trailing down whitewashed walls and beautiful cobbled roads and alleys winding through them. Strict architecture codes mean there are no modern buildings, lending the place an undeniable romanticism.

In fact, Hydra first earned its reputation for its prowess during war. Its reputation surged in the 18th and early 19th centuries for its shipbuilding capabilities, leading naval battles during the Greek War of Independence. But in 1939, an annexe of the Athens School of Fine Art opened on the island and visiting writer Henry Miller wrote of Hydra’s ‘wild and naked perfection’ in the The Colossus of Maroussi. It began to attract artists and bohemians, who congregated at cafes to imbibe and philosophise, steadily building what was to become a mystical allure around the island.

Less than a decade later, Hydra was to be left in ruins by the German occupation during the Second World War. Arriving like a shot in the arm was the film Boy on a Dolphin, starring Sophia Loren as a Greek sponge diver, in which the island’s impossibly perfect turquoise waters and rich, red sunsets were revealed on screen to the world. Suddenly everyone from John Lennon and Eric Clapton to Patrick Leigh Fermor and Lawrence Durrell were arriving in boats from Athens, wanting a taste of Hydra life.

After being introduced to the island by the Rothschilds, Leonard Cohen was one of many celebrities to purchase a home here — a whitewashed townhouse by the harbour — and was inspired to write his song Bird on the Wire. More filmmakers began to harness the beauty of its scenery in movies including Michael Cacoyannis’s The Girl in Black and Jules Dassin’s Phaedra – its rising profile in Hollywood attracting an even higher calibre of celebrities such as Brigitte Bardot and Jackie Kennedy.

Today a magnificent golden sun sculpture rises 9.1 metres high from a hillock to the left of the port, welcoming new visitors to the island. An homage to the sun god Apollo by the American artist Jeff Koons, the wind spinner perpetually whirrs as the breeze blows over the Aegean and catches the light. It is impossible to miss for any boat sailing around the island, and the decision was made by Hydra’s residents to preserve the artwork permanently following its unveiling in 2022.

Beneath sits an old stone slaughterhouse which hosts contemporary exhibitions, an outpost of the Deste Foundation for Contemporary Art, which last autumn featured the exhibition Dream Machines, co-curated by Daniel Birnbaum and Massimiliano Gioni, who have directed the Venice Biennale. Featuring celebrated contemporary and historical artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Lee Bul and Pipilotti Rist, strange, uncanny video installations meditating on the role of technology in society were installed, juxtaposed with the blue azure of the sea shimmering right behind.

Elsewhere, the island’s literary history has been encapsulated in the Hydra Book Club. Housed inside the Historical Archives Museum — located just opposite the port, honouring the island’s rich maritime tradition — the Book Club was launched by American writer and literary curator Josh Hickey in 2021. Celebrating more than a century of the island’s rich literary scene and Greece at large, it is intended as a hub that straddles museum exhibition, a community centre and a book shop featuring an evolving collection of works by iconic writers linked to the island.

The island also encourages amateur writers to make their mark. Those who wander around the narrow slips of road (there are no street names on Hydra) may discover a small, Alice in Wonderland-esque door simply marked ‘Poems’, where visitors and locals often leave their verses. Even a visit to the local pharmacy is a rich experience: founded in 1890, Rafalias is an architectural gem inside a neoclassical building decked out in Swedish pine shelving stocking glass jars of creams and potions made to time-honoured recipes, with paintings and sketches filling the walls.

All of this culture sprang, of course, of the setting. Curiously, for all its immortalisation in poetry and prose, the island is relatively barren, and swimmers and sunbathers make do with impossibly idyllic and picturesque rocks and concrete platforms. Nestled along the rocky outcrop just minutes from the port is Spilia, which derives its name from a water cave that sits just beneath the beach bar, and Hydronetta, where visitors lazily drink cocktails and watch those diving off the platform below. Further south along the coast are a series of beaches linked by a scenic coastal path. Beginning with the secluded Avlaki cove, the coastline unfolds to reveal family-friendly shores such as Kamini, Vlychos, and Plakes.

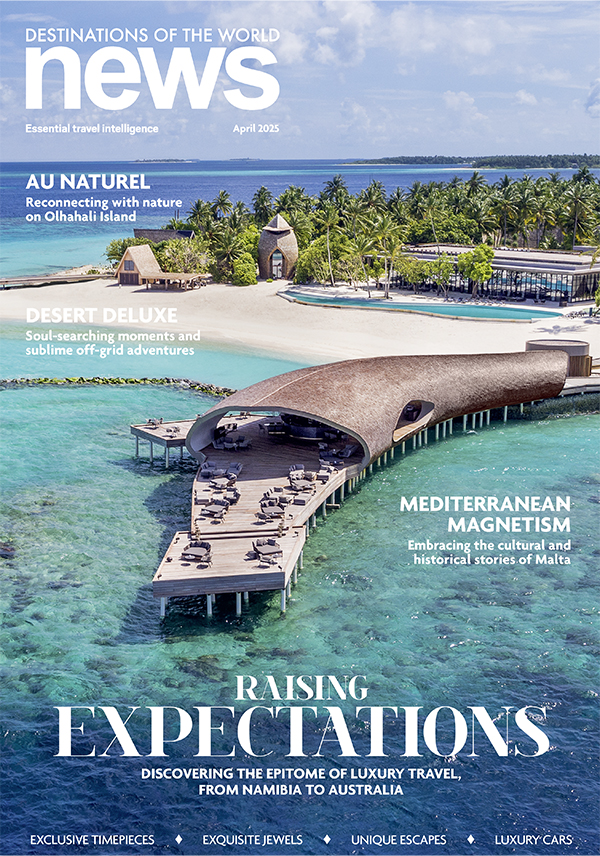

Interesting new developments increasingly speak to changes on the island. The recently opened Mandraki Beach Resort, built on the shore of one of the island’s sole sandy beaches — the bay from which Hydra launched its ships during the war in the 1800s — is a chic five-star resort with cabins with private pools, spilling out onto the shore dotted with sunbeds and umbrellas. Its intersection with its historic location is perhaps best encapsulated by the presence of the original canons, along with a small chapel on the grounds of the site. Guests are picked up by water taxi at the port, although it’s possible to walk around the path to the front of the island, where jaw-dropping sunsets await and the Greek capital feels a million miles away. Likely to draw the crowds from cosmopolitan cities who frequent Hydra on their holidays, its striking presence may see a fairly uninhabited part of the island pick up steam.

Despite its ethereal quality, the seasonal influx of visitors from the world’s most fashionable capitals means that the summer months on Hydra are lively, with packed out restaurants and bars staying open until the early hours (things are meant to wrap up at 2am, but given this is the Mediterranean, this hardly seems possible). Cocktails are taken at Amalour, a relaxed bar which spills out onto the streets on warmer days and has a small dancefloor inside, with patrons singing lustily along to Madonna and Lady Gaga.

There is also a breadth of cuisine which, as is the way in Greece, tends to be good wherever and whatever you choose, whether simple gyros or eye-wateringly expensive lobster bisque. An essential stop for traditional Greek food is Kryfo Limani, a family-run taverna inside a traditional Hydriot walled garden hidden down one the island’s winding alleys. There are also more high-end options: perched by the water’s edge is Omilos Restaurant, which has an enchanting old-world allure. Formerly known as Lagoudera, it was frequented by everyone from the Beatles to the Kennedys, with a haute take on classic Greek dishes served as small plates as waves thrash below the terrace.

In his poem Days of Kindness, Leonard Cohen asks: “Greece is a good place to look at the moon, isn’t it?’ It’s likely he was talking about the ludicrously bright moons on Hydra. An argument rumbles on about more development on the island, despite the fact that it is a protected cultural monument by the Council of Europe. Hydra today is certainly no longer a secret, but perhaps it is possible to preserve its spirit.

MANDRAKI BEACH RESORT

TEL: +(30) 22980 52110

www.mandrakibeachresort.com