Navigating the South Pacific Ocean between the Equator and the Tropic of Capricorn, the European explorers of centuries past discovered a world far removed from civilisation, a utopian paradise both enigmatic and beguiling. The islands of Tahiti, even today, are as rich in culture and tradition as they are in majestic beauty. And for the island people themselves, these are the treasures they are determined to preserve.

The 118 islands and atolls that make up French Polynesia are grouped into five archipelagos (Society, Tuamotu, Marquesas, Austral and Gambier). The most visited are the Society Islands, of which Tahiti is the largest and most populated, while the Tetiaroa atoll is a very private affair. Bora Bora’s dramatic landscape and five-star resorts attract honeymooners, making it the most touristy and least authentic, while the quieter Taha’a and Huahine islands are just as stunning – though barely touched by modern life. Island hopping aboard a luxurious, crewed catamaran with Dream Yacht Charter (+689 40 661 880) offers an opportunity to peruse the wide spectrum of blue and coastal contours beneath the clouds.

It’s equally beautiful above the clouds; even the landings and take-offs are spectacular, jetting off from an airstrip sandwiched between dense tropical forests and the coastline. Taha’a, my first destination, relies on the airport belonging to its big sister, Raiatea, to bring in the visitors. These two islands are cocooned by the same coral reef, and share the same lagoon. At Raiatea Airport, a private boat shuttles guests to the five-star Le Taha’a Island Resort & Spa, sitting pretty on Tautau motu (islet). Cruising along the lagoon, Bora Bora’s jagged peaks are silhouetted in the distance against an orange sunset.

Arriving at Le Taha’a Resort, the twinkling lights illuminating the jetty and overwater villas make everyone swoon. The lobby’s design and furnishings represent authentic Polynesian tradition. My beach villa sprawls into a main receiving area, an en suite bedroom with four-poster bed, and a lounge that opens out to a patio with a plunge pool. Every detail, down to the ancient motifs on the wooden doors, brims with Polynesian-style luxury. A road trip along Taha’a’s coast reveals an abundance of hibiscus, bougainvillaea, frangipani and camellia. Valleys and hillsides blanketed in plantations and dense jungles create a pre-historic backdrop; a vision of dinosaurs roaming the slopes wouldn’t be out of place here. My guide Aru assures me however, that other than domestic animals, there are no dangerous predators on this island.

Traffic is also virtually non-existent, so every now and again, he pulls over along the roadside to demonstrate the medicinal benefits and uses of indigenous plants. The ubiquitous coconut is the main ingredient in Polynesian cuisine, used in dishes such as poisson cru (raw fish marinated in coconut milk), while breadfruit or uru is also a staple, a commodity so important that the infamous Captain William Bligh commandeered two expeditions – first aboard HMS Bounty, which inspired the 1962 film Mutiny on the Bounty, and the HMS Providence, to stock up and transport breadfruit plants to the West Indies.

Taha’a earned its nickname Vanilla Island from the plentiful vanilla plantations, which provide up to 80 percent of French Polynesia’s supply. Compared to Madagascan and other varieties, the local variety, vanilla tahitensis, produces plumper beans with more seeds, resulting in a delicate fruity flavour and floral note. The labour-intensive process involved in producing vanilla takes up to three years, rendering it an expensive commodity. Dubbed “black gold”, its depth and complexity makes it a favourite among the world’s discerning chefs. I also have the chance to visit another farm where the skill of culturing black pearls has been passed down from generation to generation. Taha’a’s waters are conducive to cultivating pearls, an important source of livelihood for the islanders. The process of producing these translucent gems from oysters requires a high level of dexterity and precision, and is an art in itself.

Back at Le Taha’a beach, couples paddleboard their way around the tranquil lagoon, while others kayak towards the coral garden to snorkel. That night a buzz ensues high above the trees as guests ascend the stairs to Le Vanille restaurant, where every Tuesday evening a feast of Polynesian dishes is served. On an open-air platform, musicians play and girls sway their hips to the melody of the ukulele and Polynesian love songs. The pace soon accelerates to feverish hip shaking, synchronised to the rhythms of drumming, while male dancers show off their prowess with high-energy haka routines. Dance has always been a vital part of Tahitian culture, but was considered improper by the Protestant missionaries, and subsequently banned by King Pomare II in the 19th century.

Fortunately, under French occupation, this tradition has seen a revival as younger generations embrace dance to reconnect with their heritage. The Heiva I Tahiti festival held in June and July each year celebrates Polynesian life through music, dance, sports and the arts. The following day, I travel to mystical Huahine, an island of two halves: Huahine Hui (big) and Huahine Iti (little), linked by a bridge. The island derives its name from the word vahine, which translates to “woman” and represents the mountain range shaped like a pregnant woman reclining, as seen from across Fare’s harbour on Ha’amene Bay. The entire island is a tableau of verdant valleys, jungles and peaks, lagoons, dreamy beaches, lakes and bays – it’s easy to see why Tahitian royalty made this island their home. A tradition not to be missed is the feeding of blue-eyed eels that populate the streams. They are considered sacred and it’s forbidden to eat them.

Unlike Bora Bora, Moorea and Tahiti, Huahine is a piece of paradise that remains untainted by mass tourism, and not much has changed since Captain James Cook first dropped anchor in Fare. Perhaps the spirits of the ancestors once worshipped by the natives still watch over this island. During religious ceremonies held in sacred stone temples known as marae, these deities were called upon to protect the people and provide bounty during their harvest on land and sea. Huahine has the largest concentration of marae in all of French Polynesia, and several are found at Matairea Hill. The archaeological site at Maitai Lapita Village is a work in progress, and the artefacts exhibited at the museum shed light on the Tahitian ancestors, the Lapita people.

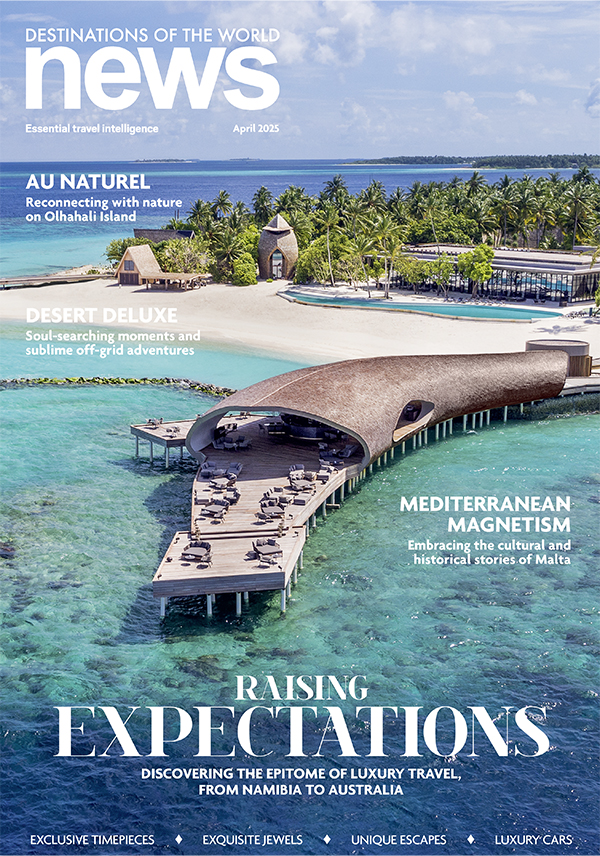

After an exhilarating sojourn in Huahine, Tetiaroa beckons. Its dreamy lagoon is encircled by 12 motus, one of which, Onetahi, was a favourite retreat of Tahitian high chiefs. Now it’s home to The Brando, possibly the most secluded five-star resort in all of French Polynesia (pictured above). This is where I reside like a modern-day royal, and it starts the moment I check in at the resort’s exclusive lounge at Papeete airport. The journey by private plane takes only 20 minutes, and we already spot dolphins in the periphery just before landing. To protect the lagoon, there are no overwater suites here, just ultra-luxurious beach villas. I leave my chilled bottle of champagne in the bucket as I inspect the media room, bedroom, walk-through dressing area and adjoining bathroom with an outdoor bathtub. Native style and contemporary elegance mingle seamlessly with the use of earthy shades, natural wood and thatched roofing, accented here and there with Tahitian arts and crafts. Privacy is also paramount. The terraced deck with lounge chairs, plunge pool, and shaded dining cabana are bordered by pandanus, coconut palms and miki miki trees for discreet access to the beach.

My culinary journey kicks off at the Beachcomber Café-Restaurant. Given the chance, I would order every dish from a menu that marries Polynesian and French cuisine, but over three days, I manage to narrow it down to my favourites: layered crab cake, scallops trilogy, Tahitian shrimps and mango spring rolls. The gastronomy continues at Le Mutinés restaurant, where executive chef Bertrand Jeanson expertly interprets the cuisine of Guy Martin, chef propriétaire of the three-Michelin-starred Le Grand Véfour in Paris. At Bob’s Bar I’m pleased to see a menu of healthy juices and smoothies. Sipping my detox beetroot cocktail while watching the fiery red sunset on a secluded beach in the middle of the South Pacific feels surreal, a bucket-list moment. It’s safe to say Tahitian princesses would have been blown away by Varua Polynesian Spa. Within a hidden Garden of Eden, spheres resembling giant nests are set high above the ground on stilts. Inside one of these treatment pods, I find a sense of calm, drifting away under the delicate hands of my Tahitian masseuse while she melts the stress away with holistic techniques.

A tour of the lagoon and motus with a naturalist guide is an education in Polynesian heritage and the environment, and the luxuries guests enjoy wouldn’t have been possible without the dedication of resident scientists at the research station. The resort’s association with the late Marlon Brando began when the actor became enamoured with the Tahitian islands while filming Mutiny on the Bounty in 1962. Determined to own a piece of Tahitian paradise, he acquired a 99-year lease of Tetiaroa in 1966, with the aim of preserving and protecting the atoll. “If I have my way, Tetiaroa will remain forever a place that reminds Tahitians of what they are and what they were centuries ago,” he said. The Brando, as it stands today, is for hedonists with a conscience and a heart for saving the planet. Reluctantly, I leave Tetiaroa, but bring back with me a better understanding and awareness of these fragile islands. I also pray that the Polynesian traditions will last forever.

Stay:

LE TAHA’A ISLAND RESORT & SPA

+689 40 507 601

www.letahaa.com

THE BRANDO

+689 40 866 366

www.thebrando.com