Vats of bubbling tamarind water, smashed piling-piling seeds and goose feathers cover the worktop. This isn’t the kitchen of some exotic restaurant, rather the busy workshop of a traditional jewellers’ in central Bali. Tucked behind Prapen’s showroom, which is set around a serene koi pond, are eight torch-wielding ibu-ibu (ladies) soldering hundreds of tiny metal granules in intricate patterns using foot-pumped bellows. This 5,000-year-old technique known as granulation is just one of the traditions reverently practised today in Bali, where visual arts is more about storytelling and religious tribute than aesthetics.

Nestled in the folds of the island’s volcanic landscape is Ubud, which has been centrum to all kinds of arts, long before Eat Pray Love put it on the map. Each of the town’s outlying villages have cultivated a reputation for a particular craft: Mas for its woodcarving; Batuan, painting; and Celuk, silversmithing.

My own artistic pilgrimage begins 10km south of Ubud in Celuk, where window-shopping along its main drag, Jalan Raya Celuk, is a portal into the world of pandais (metalsmiths). As for those piling-piling seeds, they are smashed into an eco-glue at Prapen (prapen.com), whose fourth generation owner is a member of the Pande Mas – an ancient clan of Balinese smiths, whose roots can be traced back to one of Indonesia’s most powerful empires: Java’s 14th-century Majapahit.

You can try your hand at its heritage granulation technique in a private class, browse the shelves of its library dedicated to Asian art and jewellery (the first of its kind in Bali), or shop for soka flower-designed earrings and cuff bracelets, embossed with the graceful curl of fern tendrils. You only need to look to the scale-like pattern of Bali’s ‘naga chains’ (inspired by snakes) or richly textured ‘basket weave’, which mimics the island’s pandan leaf baskets, to realise nature is the common muse. The island’s famously terraced rice fields, colourful birdlife and exotic flora haven’t escaped the painter’s easel either.

It was the influx of European painters like Walter Spies and Rudolf Bonnet that transformed Ubud into an artist enclave in the 1930s. With the help of ready-made brushes and fine-woven canvases, they invented ‘modern traditional Balinese painting’, which depicted scenes of everyday Balinese life. It was a movement endorsed by the King of Ubud, who also co-founded the Pita Maha Artist Cooperative in 1934 to promote local culture.

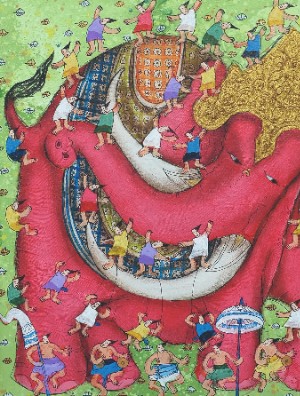

One of the island’s most iconic styles is Batuan, which draws its signature forensic attention to detail from Balinese religious rituals, as well as local folklore and mythology. Its namesake village is a bone-rattling 20-minute drive south of Ubud, where crowing roosters, tree-rustling monkeys and the unmistakable jangle of gamelan – Bali’s gong-chime orchestral music – make for a rousing welcome.

I step through the ornamented gateway of Dewa Putu Toris (dewapututorisgallery.com), where the work of some 300 artists hangs, including Ubud painter à la mode: Fachrasi Harapa, known for his pop-art style portraits, and prominent Indonesian artist Isur Soeroso, who paints realist people scenes. Digesting art in a traditional family compound (built to this day according to ancient protocols) adds another dimension to the gallery experience. Organised around a main house and temple, with alang-alang roofed open-sided pavilions (known as bales), three generations can reside in a single compound.

In one of Dewa Putu Toris’s cooling corridors I stumble across a $12,000 canvas by internationally exhibited Made Gunawan – a staggering sum considering the Balinese once regarded painting as the lowliest creative discipline. Scores of Ubud artists will still do paintings for local temples without payment as “a gift to the gods”.

Merging Batuan with Ubud style’s vibrancy is Keliki Kuan, conceived by a farmer in the ’70s, which celebrates the island’s bountiful nature on 16 x 12cm pieces of paper. You can learn to paint Bali in miniature at Keliki Painting School (keliki-painting-school.com), set in another family compound 10km north of Ubud.

Back in Ubud’s higgledy-piggledy laneways, I take refuge from another untimely downpour in its walk-in sanggars (studio-cum-galleries), before making the soggy stroll to Museum Puri Lukisan (museumpurilukisan.com) – officially Bali’s oldest art museum. Set in frangipani-scented formal gardens (even more perfumed after the rains), it’s home to Bonnet’s romanticised portraits of noble peasants, as well as a remarkable collection of woodcarvings.

One village renowned for sculpting artwork out of a single tree trunk is nearby Mas – also the literal spiritual home of Bali’s thousand-year-old mask-making tradition. Known as topeng or tapel, the island’s ceremonial masks are designed to ward off everything from evil spirits to eruptions from Bali’s smouldering volcanic peak, as well as celebrating the coming rice harvest and sacred theatre-like Barong Dance.

Sat cross-legged on his studio’s porch, third generation undagi tapel (mask carver) Nyoman Selamet sculpts the bulging eyes of a lion-like Barong mask, held in position by his dextrous feet. Rather than hanging pride of place above a mantelpiece, the sacred mask is destined for a cotton sack in his village temple, only to be unveiled in ceremonial procession. Crafted from the featherweight pule tree with 25 different tools, there are still 80 coats of paint, mother-of-pearl teeth and a buffalo-hair mane to go. It’s no wonder this undagi tapel produces just 12 a year. “I have one girl so this all stops when I do,” a sombre Nyoman tells me, taking a swig from a freshly macheted coconut. These time-honoured skills are passed down from father to son, and even Bali’s masked dancers (who have to undertake a blessing before wearing one) are exclusively male.

A family business with a reverence for local art that’s destined to continue into the next generation is Tanah Gajah, a Resort by Hadiprana, renamed in January after two decades under the stewardship of Singaporean hospitality group GHM. The sprawling five-hectare family estate-turned-luxury hideaway is planted just four kilometres from the din and dust of Ubud, though you wouldn’t know.

Flanked by a seemingly endless carpet of emerald rice paddies, it’s a tranquil oasis of lotus ponds, interconnecting lakes (graced by black swans) and immaculate lawns where hibiscus flowers are artfully tucked behind the ears of sculptured deities.

I take all this in from the 20-villa resort’s open-sided, colonial-styled lobby that’s guarded by two Ganesh statues, armoured with ancient Chinese copper coins known as kepeng. They are just several of the hundreds of artefacts curated by the family’s late patriarch: Hendra Hadiprana. The acclaimed Indonesian art collector and architect happened upon the plot on honeymoon in 1960 after visiting nearby Goa Gajah, a UNESCO-listed ninth-century temple which gave rise to the resort’s name: “land of the elephants”. Above me are a herd of flying red elephants – just one of 29 different Ganesh ornamentations scattered throughout the property.

A late lunch of sambal udang (river prawns in spicy tomato sauce) and resort-harvested rice in the dining pavilion is an opportunity to marvel another piece from Hadiprana’s renowned collection, that looks as if it’s been excavated from Pompeii. Sourced from South China, Vietnam and Thailand during the 16th and 17th century, tempayans are a type of earthenware urn used as early refrigerators, that are now highly sought after.

Fittingly called The Tempayan, the restaurant is modelled on a wantilan where villagers congregate, epitomising the indoor-outdoor living that Bali has become synonymous with. It’s a design hallmark that extends to the resort’s bird lounge and yoga shala – a prime spot to glimpse the oft-rumbling (but reassuringly distant) Mount Agung: Bali’s holiest and highest mountain.

Today it’s playing hide and seek behind a misty veil, so my cheerful butler whisks me off to Tanah Gajah’s most exclusive villa, built as a one-of-a-kind, two-bedroom estate for the architect and his wife. 150-sqm of pitch-roofed, light-flooded living and dining space is the backdrop to a museum-worthy collection of paintings and antiques, which pay homage to Bali’s rich arts heritage. The standout is Imam Sutopo’s Wayang Golek Pengantin: a diptych showing a Sundanese bride and groom on horseback being played by the hands of a puppet master.

From the AC unit artfully disguised under wooden slated panels, to the shower’s trunk stool for resting mid-scrub, thoughtful touches abound, inside and out. After some invigorating lengths of my private 10-metre swimming pool, I retreat to the bale – a Balinese sleeping pavilion, designed with guilt-free siestas in mind.

Swapping my poolside bale for a lakeside one, the following afternoon is ushered in with a Balinese picnic overlooking a swan-filled lake in Tanah Gajah’s sister property, Bumi Duadari, which means “two angels”. Reinforcing the moniker are twinned angel statues in its bale barong – the spiritual heart of the profoundly serene two-hectare estate that Hendra Hadiprana dedicated to his two daughters: Puri and Mira. Designed in tiers that mirror the island’s rice paddies, the estate tumbles all the way down to the sacred Petanu River, which I can hear in all its burbling glory from my two-bedroomed garden villa. Bedecked with lashings of local bangkirai wood, ornately carved furniture and striking art by the likes of Balinese painters Djirna and Hantaguna, it doesn’t take long for me to settle in and slip into my batik dressing gown.

Claimed as a national heritage and elevated to an art form, the centuries-old wax-resist dyeing technique may have Javanese origins, but batik is embedded in Balinese culture, where designs take inspiration from mythological creatures like the kala and fishing, inspiring the popular Ulamsari Mas pattern. The Indonesian textile also holds a deep ritual significance – babies are carried in batik slings designed with good luck motifs, whilst handmade batik tulis signify social status.

Widya’s Batik (widyabatikclass.com) hosts regular batik workshops in an airy Ubud studio, using all organic dyes like blue (indigo plant), brown (soga tree) and dark red (morinda citrifolia) versus synthetic imitations. Meanwhile, at Sari Amerta (sari-amerta.com) – a scenic half hour drive north from Ubud in Tegallalang – you can watch women apply wax with a spouted tool called a tjanting, then splurge your last rupiah on beautiful batik cushions, bed spreads, shirts other apparel in its annexed showroom.

My own purchase is a maxi dress emblasoned with an abstract version of the banana flower – a motif known as batik pisang, which symbolises hope and salvation – something that wouldn’t go amiss in these unprecedented times. I later learn (somewhat prophetically during the planning of a return trip), it also means ‘come back again’…

Stay:

Bumi Duadari

+62 361 975 950

Tanah Gajah, a Resort by Hadiprana

+62 361 975 685